John Buckley Interview

The interview that follows between Wendy Bignami and John Buckley took place via several conversations through April 2012. John Buckley is the director of the John Buckley Gallery, Richmond, and in 1984 was the inaugural director of the Centre for Contemporary Art (later known as the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art) in Melbourne. He was responsible for Haringʼs visit to Australia that year. Bignami is a contributing author to the online component of this publication and developed an interest in Keith Haringʼs mural in Collingwood after relocating to Melbourne from San Francisco in 2007. The interview details the projects undertaken by Haring during his three-week visit to Australia, the people he met while he was here and the circumstances under which the outdoor mural at the old Collingwood Technical School came about.

Wendy Bignami: You were instrumental in bringing Keith Haring to Australia for his one and only visit in 1984. How did this come about?

John Buckley: It took a while to actually get Keith Haring here to Australia. In 1982, I was on a trip to New York and was travelling by subway down into the SoHo area, where most of the art galleries were situated in those days. I noticed these chalk drawings that were being done every so often on the sheets of black paper used to paper over out-of-date ads in the subway. I noticed a whole run of these, not just at one station but at several, and was intrigued by them as they clearly were not done by an amateur. They were the work of someone who was very assured about what they were doing and I thought they had a kind of energy about them that was attractive. Later on I went into the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo and saw some large ceramic pots sitting on the floor, and it was unmistakable that they were by the same artist. That is when I first heard the name Keith Haring.

It then took some time to actually meet Keith in person because of his busy schedule. He was on his way to Documenta, the contemporary art exhibition in Kassel, Germany that takes place once every five years. I was also on my way to Documenta but I was not able to meet with him there. I then followed him to London, where he was in a group show at the ICA about a collective of New York artists involved in urban imagery and urban concerns. There I watched him do a very large piece on a long roll of paper in a very short time. He would take a space and without any preliminary thinking about it he’d just simply paint with extraordinary energy and with great rapidity these cartoon-y, bouncy figures.

I was so impressed by the sheer energy of the performance aspect of his work that I decided he would be a wonderful candidate to bring here to do a number of large-scale drawings. I am always interested in the idea of bringing artists who can do what they do here without that business of transporting things to Australia, which is an expensive enterprise. After watching Keith at the ICA I was able to eventually meet him, and his entourage, at his hotel in London and suggested the idea of a visit to Australia. He agreed and a short time later I returned to New York and visited him again. This time we discussed the arrangements for his trip to Australia and two years later, in February 1984, he arrived.

Haring spent time in Melbourne and Sydney during his three-week visit to Australia. Could you tell us about some of the activities he undertook while here?

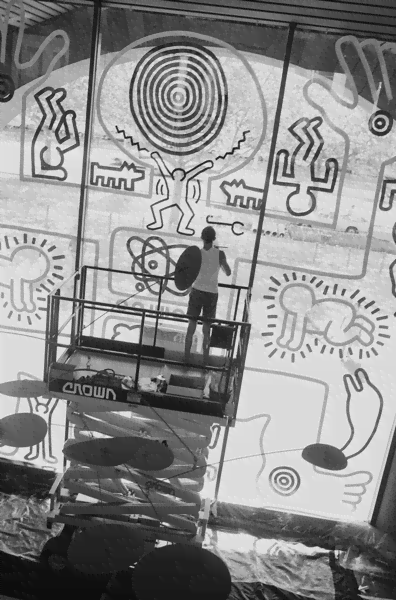

The main project Keith undertook in Melbourne was to paint the large glass water wall of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). We got Keith a scissor lift, which he loved. He’d never used one before but went on to use them again in large-scale murals he created after his trip to Australia. For four days he painted on the inside of the glass wall with his Kenny Scharf- decorated radio blaring, surrounded by interested spectators coming and going. The foyer of the NGV was crowded with school kids watching him, and Keith was signing and drawing things on arms, books and scraps of paper for anyone that wanted something. When he was finished there was an opening ceremony. Patrick McCaughey, the then director of the NGV, gave a small speech. Some days or weeks later, I can’t recall clearly, somebody fired a bullet or some kind of projectile at the water wall and part of the work was destroyed. The large glass panel in the middle was shattered and had to be replaced. The work was removed in the process.

While in Melbourne, Keith also did the angel mural at Glamorgan School (now Geelong Grammar) in Toorak. I was working there at the time and living on campus. Keith stayed with me there for a week and I suggested to him that he might like to leave something behind at the school for the children. So we lined the kids up — I think they were all sitting on the grass watching him as he worked — and he painted this simple guardian angel in what was then the kindergarten area, so it was very much for the toddlers. He painted it quickly, as he always did; it took him something like half an hour, maybe, tops. The wall that the angel appears on was then an exterior wall of an old building. No-one had the faintest idea of who Keith was or what he was doing here, but the kids were delighted to watch it being painted.

Keith also travelled to Sydney and painted the largest wall drawing that he had done thus far, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. It was in the large foyer that separates the 19th- century galleries from the contemporary hang in the court itself. I (initially) had quite a job of persuading the gallery’s director, Edmund Capon, that this was a good thing to do, but eventually I just showed him the cover of Vanity Fair, on which Keith’s artwork appeared the month he arrived in Australia, and the deal was done! This mural was also painted with a scissor lift in front of the public and was temporary, painted out before the Biennale of Sydney opened at the gallery in April that year.

While in Sydney, Keith was part of a Keith Haring float in the annual Mardi Gras parade, and in Melbourne he was also part of a Melbourne Fashion and Design event at the Moomba festival. We found a young man willing to be hand-painted with his ciphers for that event, and there was a lot of partying. He enjoyed all of that; he was a very social person.

One of the last things Keith completed while he was in Australia was the outdoor mural at what was then the Collingwood Technical College on Johnson Street, in an inner-city suburb of Melbourne. It is only years later that there is any interest in this work and the other smaller murals and drawings that Keith made throughout Fitzroy, Richmond and other inner-city locations he visited.

How did the mural, painted on the exterior wall of the old Collingwood Technical College, come about?

I think it’s likely that I contacted the Collingwood Tech and went down and spoke to the principal about the fact that we had this quite important artist out here from America. Did he have a wall somewhere that Keith might be able to do something on with the kids? Keith was always keen to work with young people.

I already have in mind when I approach somebody, I think to some extent, what that person might be able to do because I know the sort of circuit that that artist can be fitted into. I think that is one of the things about doing visiting artist projects: You do instinctively seize on something that you know is going to be exciting and interesting and workable in a practical sort of way.

Melbourne in the late 1980s was very different to the Melbourne we know today, Collingwood in particular was a far more gritty version of its current self. What did Haring make of the city? Did he have any goals or specific interests he wanted to pursue while here?

Like all New Yorkers, Keith was a fish out of water when he first arrived, and it took him a while to acclimatise to being here. He was in Australia for almost a month, and while he was incredibly generous with his time, doing everything that was asked of him, you could tell he was somewhat ill at ease. I’ve experienced this with New Yorkers before; you take them out of their own neighborhood and they are lost. They don’t travel well at all.

My role was really to facilitate Keith’s visit as much as I could. I wanted to introduce him to different aspects of the arts community in Australia.

In the early 1980s Australian artists like Howard Arkley and Jenny Watson were really just coming to the fore. There was also a huge music scene in St Kilda. There was a lot happening and it was all taking place around the Crystal Ballroom and the Hardware Club in the city. The whole punk music thing was developing; there were the beginnings of rap and a bit of a stirring of the graffiti thing happening at the same time. It was at the Hardware Club and other places where Keith hung out socially in Melbourne that he did many of his pieces. Suffice to say most of these were spirited off long ago.

It was a very social time. I recall getting a group of people together one evening at the Toorak house. It was a nice summer evening and we had drinks and so forth on a table outside and I introduced Keith to artist Juan Davila and maybe Howard Arkley. It was a very hot night and Keith later went off and had a swim in the school’s pool. He also spent time in the classrooms at Glamorgan. I had given him a key so he could go into the classrooms at night and draw on the blackboards, leaving chalk drawings for the kids to find the next morning. I remember they created all kinds of curiosity and so forth among the kids.

Introducing Keith to people in the local art community was important. He was a very social being. Early in his visit I introduced him to Mark Schaller, at the time a young Melbourne artist. I asked Mark to show Keith what was going on in Melbourne and Mark, who kept up with all that stuff, did just that. Mark was part of the Roar group that was just emerging in Fitzroy at that time. He introduced Keith to lots of other artists.

I can remember there was also a big party towards the end of Keith’s time in Australia. Paul Taylor, the writer and curator who famously conducted the final interview with Andy Warhol, was still living in Australia and hosted a terrific party on the rooftop of the block of flats where he was living in South Yarra. A clip of Keith chatting with partygoers at this event accompanies the rolling credits in the documentary I commissioned, Babies, Snakes and Barking Dogs: Keith Haring in Australia. The whole art world of Melbourne at that time was there.

We know Haring painted spontaneously and speedily; the Collingwood wall was finished in a day. Could you describe the event and energy on the ground during its making? How long did Haring study the blank wall before taking to it with paint? What was his process for choosing the colour palette?

The mural was painted on 6 March 1984. It was a warm and windy Melbourne day. All of the kids from the Tech were excited that this was going to happen. They were gathered around Keith and he, in his usual energetic style and manner, belted the mural up in less than a day.

Keith worked very quickly. The energy that he produced when he was working on a piece was infectious. He radiated energy. People loved to watch him work. In that sense, one of the reasons I decided he was an exciting person to bring to Australia at that time was the performative aspect of his work — the whole graffiti thing and the guerilla strategy that goes with it — moving into something, striking quickly and then the work is there, bang! That’s part of the excitement and part of the energy of the work too.

I never had any discussion with Keith at all about what he was going to do at Collingwood. I simply went up the road to the paint store and bought a whole bunch of Dulux paints. We met up at Collingwood Tech, set up the ladder and off he went, and that was it.

Did Haring hint at where his ideas for the Collingwood mural came from?

I didn’t know when I was first speaking to Keith exactly what he was going to do, and we never had any discussions about it. But I knew that there were going to be lots of possibilities, and I knew that they would be fairly limitless, simply because of the nature of his work.

Keith’s ideas for the Collingwood Tech mural came from the general pool of ideas that he was using as a kind of currency, if you like, in his art at that time. His imagery had already been fairly well developed from the time I met him in New York and him coming to Australia. He was already well known for the murals he was doing in and around the East Village in New York and I think he had already travelled overseas and worked there as well. The ideas that he developed in the Collingwood mural were part of his existing vocabulary of marks and signs, and images that he had been developing a reputation for.

Haring is widely known to have been incredibly sociable and exuberant. Who did he meet while in Australia and how was his visit received by the local arts community?

By the time he visited Australia Keith was already on the way to becoming a sort of superstar of the period. While his star was on the rise, however, his work was only just beginning to be known here, and then only to a small group of people. He obviously had a group of fans here, though, and they quickly gathered around him while he was in town.

During his time in Australia, Keith met a number of people and generally spent time kind of getting to know Melbourne a little bit. I introduced Keith to a number of artists and he was also introduced to some of the young artists who were part of the Roar group through Mark Schaller. They took him around and introduced him to other people in Melbourne, so by the time he left Australia he had met a number of people ‘on the run’. Keith was very much an urban person and had no interest whatsoever in spending, for instance, a day in the bush or something. That would not have interested him the slightest bit.

Tell us about the Collingwood mural from your own perspective. What is it about? What is Haring’s legacy?

I think that for Keith the Collingwood mural had some significance in terms of his relationship to what was then an emerging technology. The computer was around in the early 1980s but it was not as ubiquitous and commonplace as it is now. In terms of this particular mural, I believe he was trying to make some sort of a statement about computer technology, generally, and its relationship to ordinary patterns of living. Was this emerging technology going to change anything? Was it going to become some sort of huge, powerful and manic influence on young people?

Looking back on it now, this mural to me is a rather sad remnant of an enormously exciting period of about two weeks when Keith was here in Melbourne. In Keith’s case the work really wasn’t so much about the artist’s hand as it was about the whole performative element of mark-making. Mark-making is a very individualistic thing and there was something about Keith’s marks that were very distinctive.

As you watched Keith paint the thing there would be drips and he’d be going over things and touching up. All he was interested in was getting the image up on the wall — that bold, linear image that was going to project something that he wanted to say. He embraced the world of advertising, of printmaking, of those kinds of mediums. So I think that this must be borne in mind, and it is one of the things people forget: the spirit of the work. It is what Dennis Denuto in the film The Castle would have called ‘the vibe’. We still have the choreography of that performance there in those marks on the mural but unfortunately the energy is all gone. I think Keith, if he were still here, he’d be endorsing a repainting, he’d be the first person to say, ‘get out there and repaint it’.

My sense of Keith’s legacy would be art as a public thing and art as performance. He was very savvy about the culture that he found himself in, the whole world of pop, consumerism and the emergence of electronics. His art reflects that moment in time better than anyone I can think of.